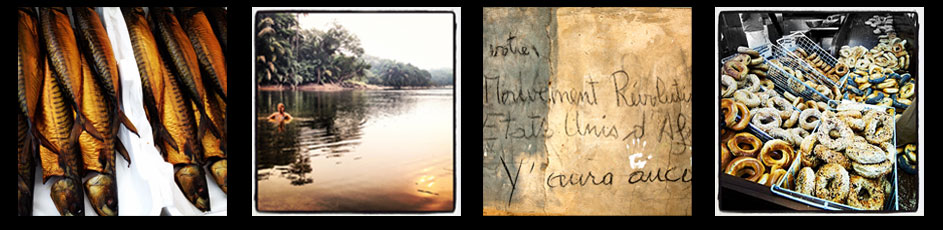

Homemade placintas from the south of Moldova, in Comrat. Photo by Leah Kieff

Placinta. The first time I tasted this traditional fried bread, still warm from the pan, I knew I would love living in Moldova. My first bite was of a Romanian-style placinta—homemade, deep-fried, filled with brinza (homemade cheese, like a drier, saltier feta) and dill—hinting at the dish’s origins in Romania, back when that country was part of the Roman Empire. Nowadays it’s everywhere in neighboring Moldova as well, in just about every alimentara (corner market/convenience store) around the country, the equivalent of a cheap, convenience-store hot dog—though when homemade, it’s also a staple at large celebratory meals.

Placinta (“plah-chin-ta”) is, simply, fried pastry-like bread with various savory or sweet fillings. Most commonly it’s filled with brinza, varza (cabbage), or cartofi (potatoes), but occasionally you’ll see apple on offer, and a handful of seasonal varieties exist. You know fall has arrived when you see boston (pumpkin) placintas, summer when you see visine (sour cherries). And though it’s typically a vegetarian dish, every now and then you’ll encounter a meat-filled placinta, called chebarech.

Savory takes are more popular in Moldova, but Romanians and some Moldovans still prepare their placinta similarly to the way they did in ancient times, when it was a flat dessert bread topped with honey and filled with sweets, usually cut into four slices and served. (This preparation makes sense given the dish’s etymology, from the Latin word placenta, meaning cake.)

Photo by Zserghei

Homemade placintas throughout Moldova vary greatly by region—in central and northern Moldova, some have light, phyllo-dough crusts that are almost spanakopita-like in texture, while others are the more typical flat and heavy placintas, for which the dough is rolled out, the filling is placed in the center, the dough is folded over, and the whole thing is deep-fried. The northern store-bought placintas tend to be bready, almost like a circular, flatter croissant with fillings throughout each layer of dough. In the south, meanwhile, the placintas nearly resemble wraps.

The ratio of fillings to bread, the thickness of the bread or dough used, whether it’s barely fried or deep-fried, the amount and type of fillings—all of these elements can vary greatly, suggesting that this snack is not quite as simple as it seems. Getting them just right is what creates the perfect placinta.

I sometimes wonder how there isn’t an obesity epidemic in Moldova with the amount of placinta that’s constantly available—and I personally blame this dish for the extra pounds I’ve picked up here. But I don’t regret a single fresh, homemade placinta I’ve ever eaten. (Note: If you're visiting Moldova and looking for a good store-bought placinta, the chain restaurant La Placinta is a safe bet, offering lots of variety in crust and fillings.)

About the author: Leah Kieff is a Peace Corps volunteer in Moldova and the author of the blog ithinkaboutthateveryday.wordpress.com.

.jpg)